Some of the earliest records of performance in the West Riding provide evidence of the dragon of Ripon Minster. In the accounts of 1439-40, the Chamberlains of this Benedictine monastery note the stipend paid to the man ‘who carried the dragon in processions on the feast of the Ascension and the three Rogation days leading up to it’:

Et in salario vnius hominis portanti draconem per tres dies rogacionum cum processione & in festo Ascensionis domini xvj. d.¹

Ten similar notices of the dragon recur in Chamberlains’ accounts over the next hundred years. Only two substantive variations occur: in 1472-3 and in 1478-9, the Chamberlains identify the carrier of the dragon by name, William Sawer and Richard Chapman respectively. In all but one of the other accounts, those for 1447-8, 1502-3, 1504-5, 1511-12, 1512-14, and 1525-6, the entry remains basically the same: payment to a man, to carry the dragon, on the three Rogation days and Ascension Thursday. The rate of inflation had no bearing on the stipend, which remained fixed at four pence per day for four days, 16 d. in all. Unfortunately the chamberlains do not describe the physical features of the dragon or its role in the processions in Ripon. A chamberlain, of course, had no need to do so; for accounting purposes what was noteworthy was only how much was paid, to whom, and for what reason.

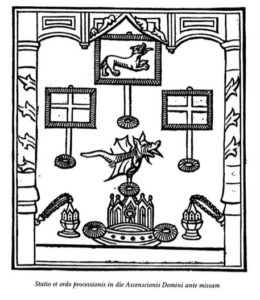

The order of the procession after the first two/three Rogation days, with the lion superior to the banners of the saints superior to the dragon.

If the Rogationtide processions at Ripon Minster followed practices of other English and European churches, the carrier of the dragon had a key part to play, for the dragon led the procession on the first two or three Rogation days. On Ascension Thursday however, and in some places on the Wednesday before, the dragon was relegated to a position following the lion that symbolized Christ and the banners of the patriarchs, prophets and the saints. The change in the dragon’s place in the procession signified the triumph of Christ over the devil. In some churches in France, the dragon’s tail told the same tale of the devil’s defeat. In the first Rogation week processions, the dragon’s tail, stuffed with straw to stiffen it, was held high. In the last one or two processions, the dragon’s tail, emptied of its stuffing, was lowered and limp.²

The final record of the dragon of Ripon Minster appears in the chamberlains’ account of 1540-41, when Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries was close to completion. The entry in the account is an odd, seemingly unnecessary one, because it registers not a payment, but a non-payment:

Et Soluto cuidam homini portant dracone — nihil.³

St. George Slaying the Dragon; wall painting from the Parish Church of St. Peter and St. Paul, Pickering, North Yorkshire. Photo credit: Mark Chambers.

The end of the Ripon dragon did not extirpate dragons completely from the West Riding. In 1635, Francis Burdet of Birthwaite noted his expenditures related to the show of light horse at Sheffield that year. Besides purchasing gunpowder and repairing ‘the great bridle’, he paid a man ‘for bringeinge the headpiece & dragone from yorke.’* The conjunction of the headpiece and the dragon suggests that the horse show that year may have included a representation of St. George and the dragon. For records of the York dragon, we have to go back to the celebration of the feast of St. George in 1554, when the city chamberlains made payments:

‘to the porters for bering of the pagyant the dragon and St christofer’,

‘to Roger walker for mendying the dragon’, and

‘to Iohn Sampler for playing St George’.†

Although we have no other evidence of performances with the dragon of York, clearly it survived for another performance in Sheffield.

Salisbury Giant (orig. 15th C.?) and Hobnob, Salisbury Museum, photo credit: Richard Avery (CC BY-SA 4.0; avail. Wikimedia Commons)

For dancing giants in the West Riding, we have to travel to Pontefract, as the poet, playwright, essayist, and writer of court masques Ben Jonson did. Early in July 1618, Jonson set out from London to walk to Edinburgh. He and his companions, escorted by a bagpiper, left Bawtry on August 7th, then spent a day in Doncaster before arriving in Pontefract on Sunday August 9th. Throughout his journey people welcomed him as a celebrity: when he arrived in Pontefract he received a buck from the Duchess of Shrewsbury, dined with one local alderman, and stayed with another. As Jonson’s companion noted:

‘all the towne was vp in throngs to see vs, And there was dancing of Giantes and musicke prepared to meete vs.’‡

Perhaps these giants were those that normally stood as keepers of the hall in Pontefract Castle. If so, bringing them out to dance on this occasion made the city’s welcome of Jonson quite special.

Ben Jonson, c. 1617. by Abraham van Blyenberch, oil on canvas, National Portrait Gallery, London; avail. Wikimedia Commons

Jonson was not the best audience however. Notwithstanding what had been prepared for his reception, he and his companions fled, taking ‘a by way to escape the Crowd’. And when ‘a swarme of boyes and others crossed over to overtake’ them, they drew their pistols ‘to keepe them backe, and made them believe [they] would shoote them to get passage’. Perhaps supper that day was Jonson’s way of atoning for his ungenerous response to an exceptionally warm welcome: ‘he invited the whole towne to his Venison’ and paid the 41 s. for the wine too.

¹ Leeds, Brotherton Library, MS Ripon 183, CR2 (1439-40), mb 2d.

² See Thomas Liszka, “The Dragon in the ‘South English Legendary’: Judas, Pilate, and the ‘A(1) Redaction,” Modern Philology 100 (2002): 50-59 for medieval commentary on Rogationtide processions.

³ Leeds, Brotherton Library, MS Ripon 183, CR 11 (1540-41), mb 4.

* Leeds, Brotherton Library, Wilson MS 295/62 (1635), f 10.

† York, ed. Alexandra F. Johnston and Margaret Rogerson, Records of Early English Drama (Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1979), pp. 319-20.

‡ Quotations are from the Aldersley MS, Cheshire Record Office, Chester, CR 469, ff 8v-9. We are indebted to James Loxley, Anna Groundwater, and Julie Sanders who discovered the manuscript, brought it to our attention, and published a superb edition: Ben Jonson’s Walk to Scotland: An Annotated Edition of the ‘Foot Voyage’ (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015). See also the website (<https://www.blogs.hss.ed.ac.uk/ben-jonsons-walk/>) developed by the ‘Ben Jonson’s Walk’ project.

⇒ This month’s Flower is brought to us by the REED Yorkshire: West Riding co-editor Ted McGee.