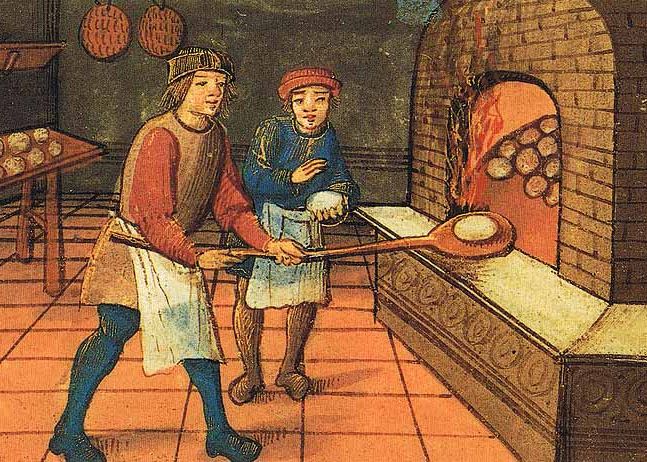

A soul cake was a small cake or bun specially prepared for All Souls’ Day (2 November). A tradition of ‘Souling’, an ancestor of ’trick-or-treat’, can be traced back to the 16th century. The poor would stage music, song, or theatricals in return for a cake, which would help the soul of the benevolent giver. It was mainly a tradition in northern and western England—and we need your baking skills to bring it back to life in our region today.

Have a go at a technical challenge with a historic recipe, or see some modern soul stopping masterpieces submitted to our competition that ran during 2018. Even though the competition itself is closed, you can still share your technical or soul stoppers and we’ll post them to this website. Or tweet your own masterpiece via #SoulCakeBake.

Technical Challenge – help us work out how a 16th-century recipe might have been baked, following only basic information

Technical Challenge – help us work out how a 16th-century recipe might have been baked, following only basic information

Soul Stoppers – try some modern reinterpretations of soul cakes sent in by readers

Soul Stoppers – try some modern reinterpretations of soul cakes sent in by readers

A brief history of soul cakes

The sweet is connected with ‘Souling’. ‘Souling’ belonged to a range of seasonal practices of begging for food or drink with song, music, or small-scale theatricals. The tradition of ‘Souling’ was chiefly known in northern and western England; for instance, in Shropshire, All Souls’ Day was called Souling Day. In 19th-century Wales, poor women visited their wealthier neighbours, demanding ‘soul’. A similar custom was ‘catterning’, which took place on St Katherine’s Day, 25 November, and involved especially women. Katterners (mummers) went round begging for apples and beer, and singing, celebrating a female saint in this way.

An early reference to giving soul cakes to singers or mummers comes from the Protestant pamphleteer Philip Stubbes, who, in 1593, counted the practice among the examples of Catholic superstition, and called upon all ‘Papists’ to abandon such customs to ‘the devil their author’:

To give soule-cakes (for so they shame not to call them) or rather foole-cakes agaynst all soules daie, for the redemption of all christen soules, as they blasphemously speake. (Philip Stubbes, Motive to Good Works, iii.124)

Despite such criticism, the custom persisted.

Take flower & sugar & nutmeg, & cloves & mace & sweet butter & sack & a little ale barm, beat your spice & put in your butter & your sack, cold, then work it well all to gether & make it in little cakes & so bake them, if you will … you may put some saffron into them or fruit (Elinor Fettiplace’s Household Book, compiled around 1604)

This early recipe comes from Oxfordshire; it survives in a household book compiled by Lady Elinor Fettiplace around 1604. It involves ‘ale barm’ (a fermenting agent, ale froth), and sack (dry white wine from Spain, possibly sherry). As the quantities aren’t given, it is not clear whether this cake is supposed to rise like a bun, or bake more like shortbread.

In the mid-18th century, it was still usual for the poor, upon on All Souls Day, to go from one village to another, begging soul cakes, which were freely dispersed by many good Protestants. In the 18th century, table-boards with a heap of soul-cakes were apparently set up in parts of Lancashire and Cheshire. John Aubrey, the Oxford antiquarian, mentioned souling songs around 1697: ‘There is an old Rhythm or saying, A Soule-cake, a Soule-cake, Have mercy on all Christen soules for a Soule-cake’. A Souling Play survives from Antrobus, Cheshire: it was intended to for performance on 2 November, and features, among others, devils, a pole horse with a skull, and a song begging for soul cakes.

Historians often think of the custom as the ancestor of trick-and-treat. At the turn of the 19th century, children went ‘a-souling’, as recorded in Shropshire.

Another meaning of ‘souling’, first recorded in Old English and now obsolete, meant ‘the giving up of the soul’, or dying.