He maketh mention of a dauncer, a poore mans sonne, borne in this Citie, yet proude, & insolent, and lately made a Recusant, and by his daunceing crept into manie houses, and his wife a younge woman (being base Recusants) haue done much harme and might haue done more…

The transcript above is from a letter from Bishop James to the Archbishop of Canterbury, George Abbot, about the Robert Hindmers case. (Cal. State Papers 1611-18. MS SP 14/81, f.92)

During the sixteenth century, Henry VIII began the process of the Reformation: monasteries were famously dissolved, but other changes threatened many cultural traditions that were based on the traditional Catholic faith. Biblical plays came under suspicion because their message was unreformed, and many processions and other customs performed on feast days such as Corpus Christi were endangered by Edward VI’s abolition of the very feasts they celebrated. Records from York, for instance, show that its mystery plays began to be performed less often; then the texts were called in for examination by the ecclesiastical authorities – and finally, in 1572, the York Cycle ceased to be performed.

All over England, from the time of Queen Elizabeth, it became an offence not to attend Anglican church services; those who did not, called ‘recusants’ (literally, ‘refusers’), were punished.

In 1615, the Bishop of Durham, William James, imprisoned Robert Hindmers, a recusant dancer born in Durham who toured with his wife Anne, entertaining households throughout the county. We don’t know their itinerary, nor what kind of dances they performed; but we do know that he was supported by the Catholic community – among them William Southerne, a priest later to be martyred in Newcastle. Probably Robert Hindmers was imprisoned not for his dancing, nor even simply for recusancy, but for using his dance tours to gain support for English Catholicism.

Dramatic disputes

The Rev. Peter Smart, Puritan Prebendary in Durham (left), accused Bishop John Cosin (right), who practised a more traditional form of worship, of turning

the Sacrament itselfe…wel neere into a theatricall stage play, that when men’s mynds should be occupied about heavenly meditations of Christ’s bitter Death and Passion, [and] of their own sinnes,… theire ears are possest with pleasant tunes, and their eyes fed with pompous spectacles of glittering pictures, and histrionicall gestures…

For us, it is remarkable that, to a strict Protestant reformer, the old religion itself should seem to be a performance!

People could be accused in the Church courts of unseemly behaviour on Sundays – which in some cases meant carrying on traditional customs: Robert Hewetson was reported in 1603 ‘for makinge a may game on the Sabbaoth daie’ (Act and visitation correction books of archdeacon of Durham).

However, another accusation made by Peter Smart against John Cosin in 1630 shows that local people determinedly carried on their May Games well into the seventeenth century: he mentions ‘an old, rotten ridiculous robe used by the boys and wenches of Durham above 40 yeares in theyr sports and May-games’. The robe belonged to the Cathedral.

More cakes and ale!

So religious change certainly did not mean the end of cultural life. In Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, the reveller Sir Toby Belch taunts the Puritan Malvolio: ‘Dost thou think, because thou art virtuous, there shall be no more cakes and ale?’ In the play, the festive spirit triumphs over Malvolio’s repressiveness. In Durham, people kept their appetite for shows and marvels, including worms and dragons! In 1569 the parish register of St Nicholas’ Church notes an exciting event: an Italian showman brought a fearsome and ‘monstrous’ man-eating dragon from Ethiopia, sixteen feet long, to thrill local people – though not to frighten them too much: it was already dead. We are not told which ‘whole countrey’ it had destroyed!

London and the North-East

In 1576, actor-manager James Burbage built the first purpose built theatre in London called The Theatre. Soon many more permanent playhouses were built in London, sparking an unprecedented cultural phenomenon in English theatre history. By the 1590s the London theatre scene with its permanent playhouses, repertory system and fierce competition was marked by increasing commercialisation of dramatic art – very different from the old traditions of religious community theatre.

Was the North-East being left behind? Evidently not: records from our region in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries show that its cultural life remained lively and innovative. London musicians and acting companies toured Yorkshire, Durham and Northumberland, performing in towns and at great houses such as Londesborough, East Riding.

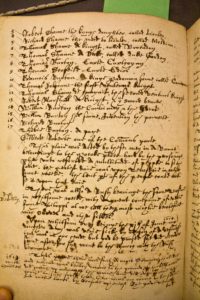

This page from the Londesborough accounts shows payments of between 10s. and 30s. to groups of musicians (from Hull and York) and several companies of touring players including Lord Derby’s and ‘a Companie goeing by the name of the Kinges players’.

This page from the Londesborough accounts shows payments of between 10s. and 30s. to groups of musicians (from Hull and York) and several companies of touring players including Lord Derby’s and ‘a Companie goeing by the name of the Kinges players’.

| 1624: | Rewardes In generall. | |

| december. | Ite{m} w{hi}ch was given in Rewarde the second day of december to a Companie of Players my Lo{rd} of Darbie his men,those came to Londsborough but werenot suffered to Play |

x s |

| viijth. | Ite{m} given his day in Reward to a Companie of Players whoe came to Londsbrough and played one play, they being my Lo{rd} of Thoumond his men. Thirtie shilling{es} |

xxx s. |

| xxth. | Ite{m} given this day in Reward by my Lo{rd} Clifford{es} Commandm{en}t to Dicke Watkinson, when he was to goe from Londsbrough to Skipton fyve shilling{es} |

v s. |

| decemb{er} | ||

| 23th | Ite{m} given this day in Reward to Mr Crosland{es} man that brought a doe w{h}ch was sent for by my Lo{rd} Clifford. v s. sent to the keeper for his |

xvij s. vj |

| d. |

rewarde — x s. and given to Ned Mason for his Charges to Helmsley w{i}th a letter to bespeake the said doe — ij s. vj. d. in all —- |

|

| 29th | Ite{m} given this day in Rewarde to three musitions of Hull, that plaied at the gates and in the house |

ij s. vj d. |

| Ianuary the first./.Ite{m} |

given this day in Rewarde to my Lo{rd} of dumbarrs keeper, whoe brought a brase of does from his Lord to my Lo{rd} & my La{dy} Clifford, in golde twentie twoe shilling{es} |

xij s. |

| 4th. | Ite{m} given this day in Rewarde to a Companie of Players, goeing by the name of the King{es} Players, whoe came hither to Londsbrough & played three tymes. three pownd{es} |

|

| viijth | Ite{m} given this daie in Rewarde to the musitions of yorke being .vj. whoe were sent for to londsb{orough} by my Lo{rd} & my La{dy} Clifforde, and were here a weeke w{i}th their Instrument{es}, attending their honors service, soe given then fyve powndes |

v li. |

| £12-7-0 | Sum{ma} pag{inae] xij li. vij s. | |

| August the ijth. |

Ite{m} given this day by my Lo{rd} Com{m}andement to the boyes of the Revells whoe plaied a play before my Lo{rd} |

xl s. |

| Ite{m} given the same day to the wait{es} of dancaster whoe plaied vpon their instrument{es} dureinge the tyme of the play |

v s. | |

| vijth. | Ite{m} deliu{er}ed this day to Stephen domis xxxiij s. in full dischardge of the Charge of Coles lead in q’. & for other his Charges in the same busines. as apeared by a note |

xxxiij s. |

| xijth. | Ite{m} paid this day to Iacke ffootman for his Charges to Beaver Castle w{i}th letters to inquyre about my Lo{rd} Rutland his com{m}ing to Skipton |

x s. |

| xiij th | Ite{m} paied this day to ffraunc{es} wood of Londsbrough for xxijtie yeard{es} of Linnen Cloth bought of him by my La{dy} Com{m}andment for Sheetes. at xiij d. p{er} yeard Sum{ma} pagine Cxiij s.viij d. |

xxv s. viij d. |

Local attractions

Locally-based companies performed the same up-to-date repertoire as could be found in London: The Simpson players, a touring company from Egton, North Yorkshire, were organised on the same lines as London professional companies and performed the same repertoire. At Gowthwaite Hall, Nidderdale, during Christmastide of 1609/10 they performed a saint play, St. Christopher, as well as recently printed works including Pericles, Prince of Tyre (by Shakespeare and Wilkins), and King Lear (possibly Shakespeare’s).

Locally-based companies performed the same up-to-date repertoire as could be found in London: The Simpson players, a touring company from Egton, North Yorkshire, were organised on the same lines as London professional companies and performed the same repertoire. At Gowthwaite Hall, Nidderdale, during Christmastide of 1609/10 they performed a saint play, St. Christopher, as well as recently printed works including Pericles, Prince of Tyre (by Shakespeare and Wilkins), and King Lear (possibly Shakespeare’s).

Even in parishes, new plays were being performed by local groups: Richard Shann’s Commonplace Book records a play in Methley, West Riding, at Whitsun 1614, called ‘Cannimore and Lionley’, which attracted ‘a multitude of people’. The play has not survived, but Richard Shann did record the cast list!

Even in parishes, new plays were being performed by local groups: Richard Shann’s Commonplace Book records a play in Methley, West Riding, at Whitsun 1614, called ‘Cannimore and Lionley’, which attracted ‘a multitude of people’. The play has not survived, but Richard Shann did record the cast list!

1614 A stage playe

This yeare 1614. A verie fyne Historie or Stage plaie called Cannimore and Lionley. was Ackted by xvijth men & boyes vpon Monday Twesdaie, Wednesdaie, and Thursdaie in whitsonne weeke, the names of the plaiers was these =

Richard dickonsonne. the Kinges partes. Graniorn & Padamon.

francis Shanne the kynges sonne.

Robert Shanne the kynges daughter. called Lionley.

Richard Shanne the maid to lionley. called Meldina.

Thomas Shanne A kinght.* called Brocadon.

Thomas Shanne A Duke, called duke Gordon.

Thomas Burton. Earle Carthagan.

Thomas Scofeild. Earle Edios.

Francis Burton. [A] kinge Padamon sonne called Canimore

Thomas Iobsonne the first ventrous knight.

Thomas Shann de hungait. the second ventrus knight.

Robert Marshall A knight, & ye sword bearer.

William Burton the Cuntri man & the Ideote.

William Burton his sonne. Invention the paracite.

Richard Burton

Thobie Burton. A page

Gilberte Roberte one of the Commans parte.

This plaie was Acted by these men in A Barne belonginge to the Pocoke place hard by the parsonage. wher vnto resorted A multitude of people to se the same. the greatest daie was vpon Tewsdaie in whitsonne weeke. the tent parte of the people could not se it vpon that daie”

*kinght] for knight

A Note on Richard Shann

Richard Shann (1561-1627) kept his commonplace book as an annual recording of national events, weather conditions, herbal plantings, local occurances, outbreaks of measles, good and bad crops, international news, lawsuits, and his family pedigree, starting in 1422 with Robert Shann, parish priest of Methley. He notes that his father, William Shann, was “verie light and lyvelie in his youth, and would runn verie faste, his greatest delyte was in musicke, he coulde plaie on Organs & virginalls . . .” (f 83v).

Writing his own obituary, Richard describes himself as “verie light and Nimble of foote, his chefest delite [being] . . . in plantinge and grafting all manner of herbes & trees. . . .” He practised physic and surgery, made illustrated books of herbs, and compiled a book of prayers and meditations. He also wrote on medicine and surgery; and “when he was three score and two yeares oulde, he made A booke chroniclewise (which he gethered out of verie Ancient Authours, and allso those of later tymes which was of good creditt.) of manie notoble thinges which happened in anie Age of the wourld” (f 84v).

Here Richard’s hand ends; his son Thomas finishes the entry with an account of his father’s death, his burial with his father and grandfather under the stone of the Lady Choir end of the Methley churchyard, and the notation, “He dyed A Romaine Catholicke” (f 88). Included also in the commonplace book are numerous “pretie songes,” some with musical notation and at least one, “A Christmas Carroll maid by Sir Richard Shanne, priest, to be sonnge at the same tyme” (ff 135v-36v), composed by Richard’s uncle (d 1561).

What now?

In the last few decades, many of the old plays, music and dances have been rediscovered and reinvigorated to become once again part of our own culture: early music, mystery plays and morris dances are all performed regularly in our region. Here are a few examples.

[slideshow_deploy id=’2928′]