The History of the Lambton Worm and Sockburn Worm

The North East is awash with folk stories, songs and lore which hark back to a murkier time and place in the past, often beyond record. An extremely rare surviving account of a dragon in County Durham comes from the St. Nicholas Church in Durham city, where the parish register for 1569 records that:

A certaine Italian brought into the Cittie of Durham the 11th Day of Iune in the yeare aboue sayd A very greate, strange & monstrous serpent in length sixxteene feete, In quantitie of Dimentions greater than a great horse. Which was taken & killed by speciall pollicie in Æthiopia within the Turke’s dominions. But before it was killed, It had deuoured (as it is credibly thought) more than 1000 persons And also destroyed a whole Countrey.

We have little idea what kind of creature this ‘strange and monstrous serpent’ really was, or how serious the writer could be in thinking that it had devoured over 1,000 people, or destroyed a whole nation. Yet accounts of this Italian traveller and his curious creature feed into a folk tradition of foul serpents, worms, and dragons active in the county since before the time of the Norman Conquest.

In the North East, tales of dragons (known as ‘worms’) seem to have dominated the popular imagination, with at least twenty separate stories recorded in Northumbria, Co. Durham and Yorkshire alone. But I want to focus on two of the most famous dragons to terrorise the relatively small county of Durham: the Sockburn and the Lambton Worms. Both stories provide a legendary origin for families once prominent in Co. Durham, yet they also demonstrate the changing functions and values attached to such folk narratives which, whilst appearing as old as time, are repeatedly moulded and re-packaged to suit the interests and principles of their tellers.

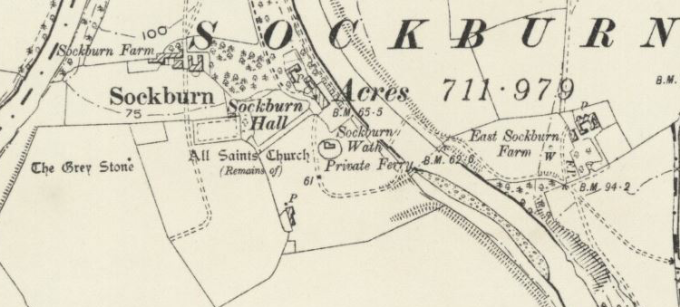

Although today the Lambton Worm is easily the most well-known of the Co. Durham dragons, this appears not to have been the case in the Palatinate during the late medieval and Early Modern periods. During these tumultuous times of religious and social upheaval, the story of the Sockburn Worm reigned supreme, telling the story of a young knight named Sir. John Conyers, who fought to save his lands from a great dragon who had haunted the region for seven years. After offering his prayers at a nearby chapel, Sir John slew the foul-breathed serpent with his trusty falchion, letting its decimated body rest in the River Tees. He buried what was left of the beast under the great ‘Grey Stone’ still visible today, and received the lands of Sockburn for his efforts from the Bishop of Durham.

Sr. Jo. Conyers of Storkburn [sic] Knt who slew [th]e monstrous venoms and poysons wiverns Ask or worme which overthrew and Devourd many people in fight, …yet he by the providence of god overthrew it…

The reputation and pedigree of the Conyers family was firmly linked to the dragon their ancestor had slayed. The Sockburn Worm was tied to the ceremonial ritual of the Palatinate. The Conyers heir was tasked with offering the famous falchion – a blade now held in Durham Cathedral’s Treasury – to any new Bishop of Durham as he crossed the River Tees at Sockburn. Bishop Cosin records the pomp and excitement associated with the ceremony in 1661:

The confluence and alacrity both of the gentry, clergy and other people was very great, and at my entrance through the river Tees there was scarce any water to be seen for the multitude of horse and men that filled it, when the sword that killed the dragon was delivered to me with all the formality of trumpets and gunshots and acclamations that might be made.

The Conyers family had been prominent landowners in County Durham since before Conquest, and the story of the Sockburn worm only helped to bolster their position in the region, providing a means for chivalric self-fashioning, as well as popular identification and admiration. When local author Anne Wilson wrote Teisa, published in 1778 in praise of the River Tees, she made reference to the noble history of the Conyers, likening Sir John to the classical figure of Hercules (Alcides):

…a deliverer to the oppress’d

Arose, whose names was Conyers, he a wight,

Did, like Alcides, in great deeds delight;

In his own prowess wrapt, and coat of mail,

He with his sword this serpent did assail…

Yet by this time, the fortunes of the Conyers family in County Durham had fallen considerably. By the late 17th century the Sockburn estate had been sold off to the Blackett family of Newcastle, a family of wealthy industrialists, and in 1809 the 9th Baronet, Sir Thomas Conyers, was found living in a workhouse in Chester-le-Street. A local rhyme best records the family’s decline:

Sockburn, where Conyers so trusty

A huge serpent did dish up

That had else ate the Bishop,

But now his old falchion’s grown rusty, grown rusty.

But with the fall of the Conyers another family, of some great age if not pedigree, was waiting in the wings with their own worm story. The first surviving account we have of the Lambton Worm – now undoubtedly one of the most famous folk tales in County Durham – comes as late as 1785, when the solicitor and antiquarian William Hutchinson (a native of Barnard Castle) discusses a hill near Fatfield Staithes, in the parish of Washington:

Near this place is an eminence called the Worm Hill, which tradition says once possessed by an enormous serpent, that wound its horrid body round the base; that it destroyed much provision, and used to infest the Lambton estate, till some hero in that family engaged it, cased in armour set with razors…the whole miraculous tale has no other evidence than the memories of old women…

At the beginning of the thirteenth century the Lambton family were members of the local ‘squirearchy’: respectable and landowning, but lacking any great wealth or prominence. During the later sixteenth and seventeenth century the Lambtons’ wealth grew just as families such as the Conyers declined – mainly due to shrewd investments in newly available land, and involvement in the burgeoning coal industry. By the latter half of the eighteenth century the Lambtons were one of the richest families in the region, and regularly held positions in Parliament as representatives of the city or the county.

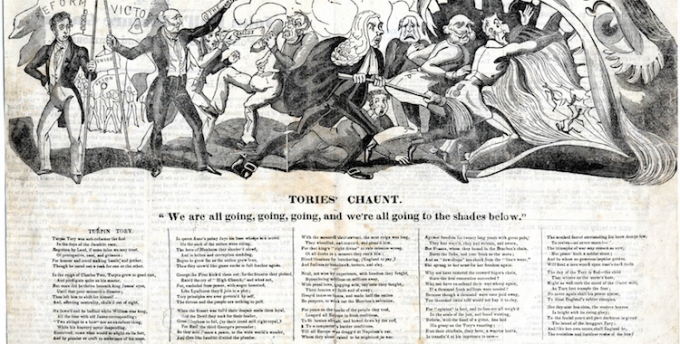

The young and dashing John George Lambton, inheritor of the immensely wealthy Lambton Collieries as well as the grand Lambton Hall, near Chester-le-Street, became Member of Parliament for County Durham in 1812. John George occupied a position to the extreme of the ‘Whigs’ or Liberals, often referred to as ‘Radical’. From early in his political career he favoured instigating large-scale political reforms, including the secret ballot, fixed-term parliaments, and universal suffrage. Although these are the norm today, at the time they were viewed as dangerous and subversive ideas, holding the potential for major social disruption.

John George regularly gave speeches calling for these popular reforms across the country, calling for the rights of the masses. He’s well-known for a barnstorming speech given at a county meeting held in Durham on 21st October 1819, decrying the political establishment’s support of the Peterloo Massacre, where soldiers had charged at peaceful protesters earlier that year. His speech was much-criticized by local conservatives, and received the ire of the Rev. Henry Philpotts, a prebendary of Durham Cathedral.

A popular ballad which was printed and circulated in the North East survives to demonstrate popular support for Lambton and his father-in-law Lord Grey, another local figure who helped lead the radical side of the Whig party:

… And as for ‘squire Lambton, that loyal young man,

For the rights of the poor he’ll do all that he can,

Here’s health to ‘squire Lambton, and likewise Earl Grey,

Who fight for the rights of the poor ev’ry day…

In 1828 John George was raised to the peerage as Baron Durham, and when his father-in-law Lord Grey became Prime Minister, Lambton was instrumental in designing the great Reform Bill of 1832, which paved the way for further reform of the British Parliament. John George became 1st Earl of Durham in 1833, gaining the noble title his family had lacked for centuries.

The story of the Lambton Worm seems to have gained real popularity during these first few decades of the 19th Century. At least three chapbooks – cheaply made mass-produced pamphlets – containing the story of the Lambton Worm were printed in the late 1820s and 1830s; many included dedications to John George, or the Earl of Durham.

The story, set in a hazy medieval past, begins with a young squire named John Lambton, out fishing on the Wear during the Sabbath. He manages to catch only a foul eel-like creature, which he hastily discards in a nearby well. The young man leaves to fight in the Holy Land and earn his spurs, but on returning home after many years, he finds the creature has grown to an enormous size, devastating the county and wrapping itself around a hill next to the Wear. After consulting a local Wise Woman, Sir John dons armour bedecked with razor-sharp spikes and vanquishes the worm, whose body is cut to shreds by the barbs. Sir John Lambton saves the people of he region from the foul creature, with great effect on the fortunes of his family for generations to come.

It is easy to draw connections between the Lambton Worm and popular support for John George Lambton. Early versions of the story tend to stress the position of Sir John as a defender of the poor, and of the people of County Durham. This reflects a strain of early 19th Century Romanticism which considered the medieval period to be a lost era, where the rights of normal English people were protected by local lords, ennobled by their liberty. Reflections on the Middle Ages at this time were formed as a response to the Industrial Revolution and an increasingly urban and utilitarian (or ‘Gradgrindian’) world. The Earl of Durham, like his legendary ancestor, was a defender of the people of county, even if he was owner of the largest collieries in the region.

The Lambton Worm’s popularity in chapbooks, and later in local ballads, poems, and plays, seems to reflect the Earl of Durham’s popular reputation as a champion of the rights of those outside the political elite. Yet the popular nobleman’s life was to be short-lived. After the tragic deaths of his first wife and several of his children, John George died at the age of 48 and was buried in the family vault at Chester-le-Street.

Testament to the way in which the Lambton Worm story had caught the imagination of the wider public came in 1867, when The Tyne Theatre and Opera House were looking for a subject for their Christmas pantomime. Inspired by the story, C.M. Leumane, a local tenor who had won national fame starring in Gilbert and Sullivan operas, penned the famous ‘Lambton Worm Song’ – still known, loved, and oft-recited in the region today. But rather than wrapping itself around the traditional ‘Fatfield’ or ‘Worm Hill’, in Leumane’s version of the story the Lambton Worm sits atop the site of the Penshaw Monument; a fitting tribute to the man memorialized there, who seems to have driven the popularity of the tale right into the present day:

Whisht! lads, haad yor gobs,

Aa’ll tell yer aall and aaful story,

Whisht! lads, haad yor gobs,

An’ Aal tell yer ’bout the woorm.

This post was originally published on READ: Research English At Durham, and was edited by Laura McKenzie.